Good Maintenance

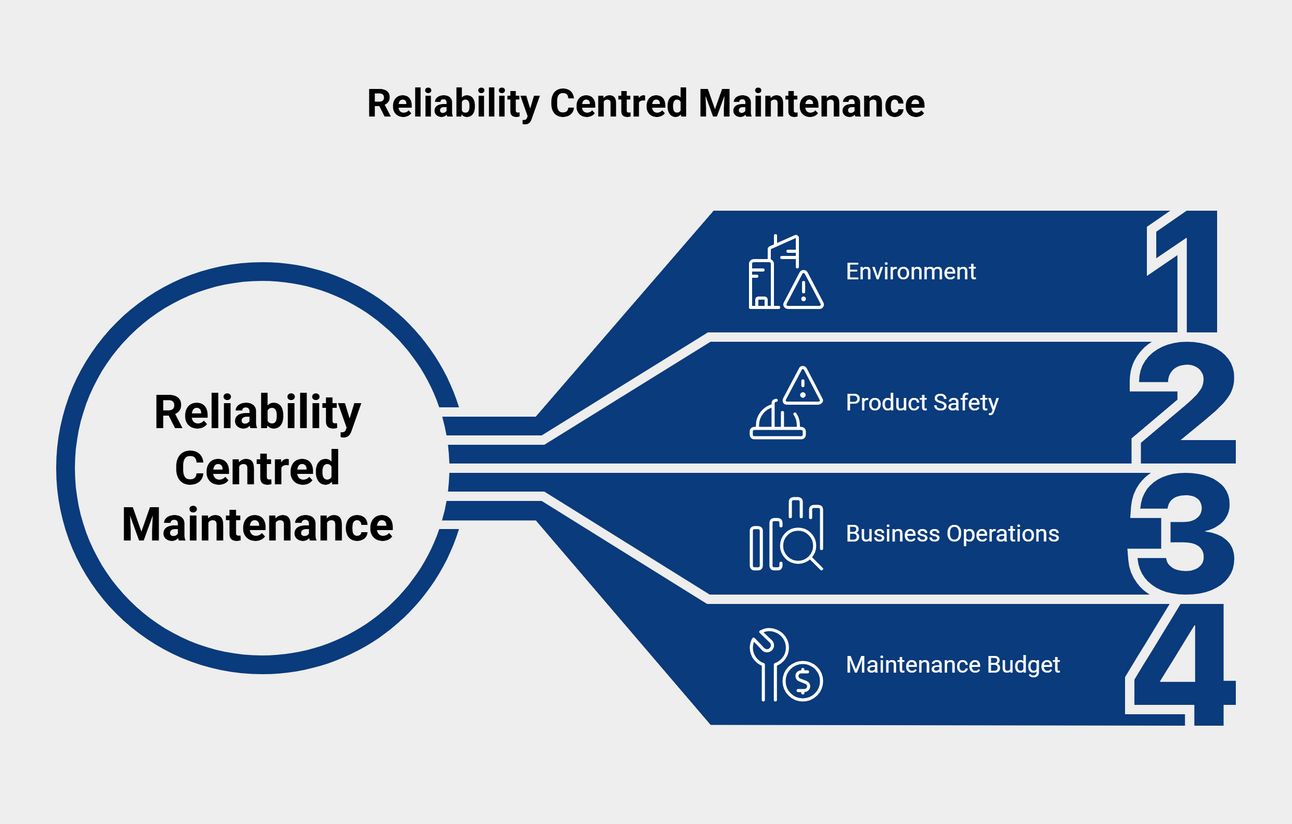

Reliability Centred Maintenance is a rational approach to maintaining products that guides practitioners to the minimum maintenance required for the product to meet its objectives. Your product needs to balance risks that are external to the product (environment), intrinsic to the product (safety), business operations and the maintenance budget.

There are two common pitfalls in the world of maintaining your products in the field:

More maintenance is better. Even ignoring the cost of maintenance interventions, this is not true. Just last year my car came back from its MOT with an MOT pass but a cracked windscreen – every intervention and use carries a risk of inducing a failure.

Quality trumps all. This is a slippery slope to saying all failures need to be resolved immediately, regardless of cost or customer impact. Good quality is not necessarily the same as high quality.

The Seven Questions

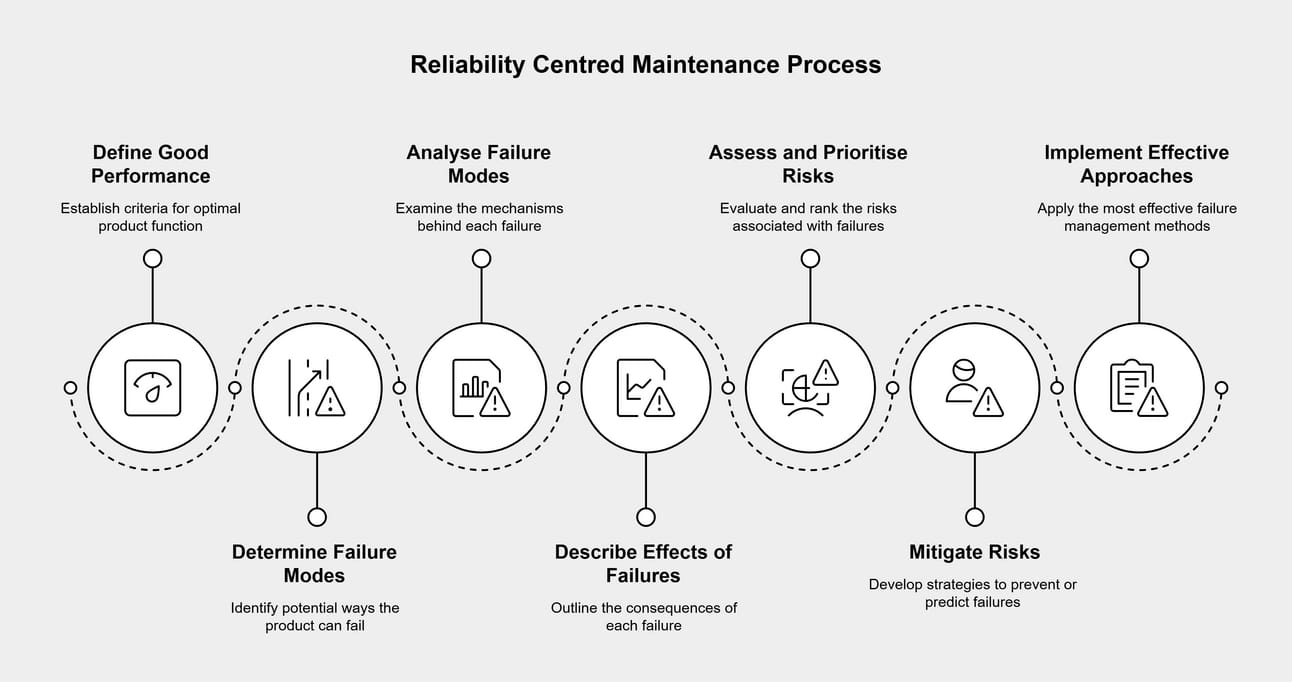

Following the Reliability Centred Maintenance approach, you need to ask seven questions about your product. Some of these are obvious and many businesses follow this to some degree. The later questions are where your organisation’s focus on maintenance (or lack of it) will become evident:

Define the ‘good’ performance of the product within its use context

Determine how the product can fail to function to that level of performance

Analyse the failure modes by which functional failures occur

Describe the effects, direct or indirect, of those failure modes

Assess and prioritise the effects to evaluate the risks

Study how those risks could be mitigated through prevention or prediction

Implement other approaches to failure management if they are more effective

Design engineers will see the similarity between the first five questions and Failure Modes and Effects Analyses (FMEAs). Production engineers will see the similarity between the last three questions and Single Minute Exchange of Die (SMED)

The full standard on Reliability Centred Maintenance (SAE JA1011) is proprietary but there are many more in-depth articles if you want to learn more about the process SAE JA1011 Standard

Maintenance Strategies

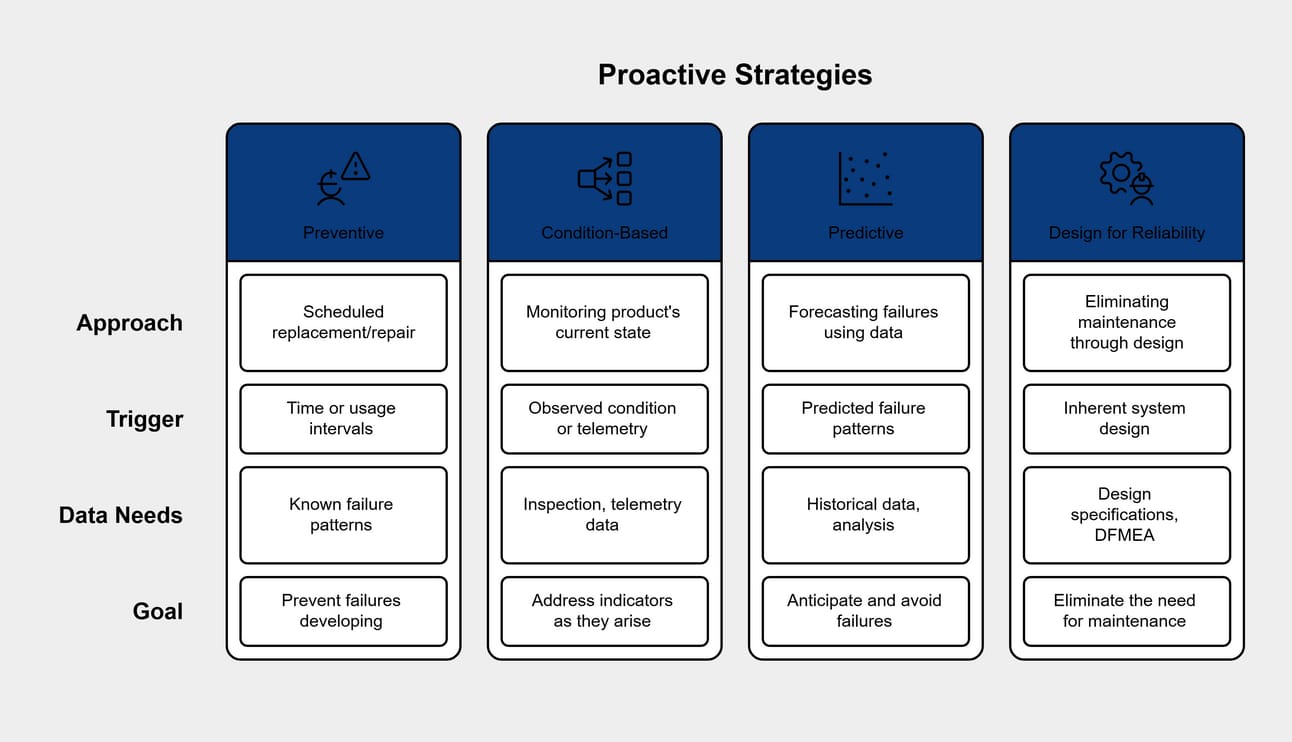

There is no universally agreed definition of different types of maintenance. For simplicity, this is a glossary of different approaches to choose in answering questions 6 and 7.

Proactive maintenance is intervention before the effects of the failure are felt. This may also be known as planned maintenance.

Preventive – this is, on a regular schedule replacing/repairing parts based on a known failure pattern. This can happen on time or use intervals determined during the design phase. Inspections may be scheduled preventively to enable a condition-based assessment.

Condition-based – this is a more focussed version of preventive maintenance, in which the current state of that specific product, whether seen through inspection or telemetry. Indicators used may be early signs of the failure (e.g. cracks in an engine casing), or independently observed but correlated (e.g. contaminated engine oil).

Predictive – failure patterns in the population or in the history of that specific product may be used to predict failures before any observable signs can be determined. This requires significant data collection and analysis to show results.

Design for reliability – although this isn’t strictly a form of maintenance, if you can design a perfectly reliably system then maintenance won’t be necessary. Even with a well-understood system this is an aspirational goal and requires the onus of failure mitigation to rest with the Design FMEA (DFMEA) rather than the Process FMEAs.

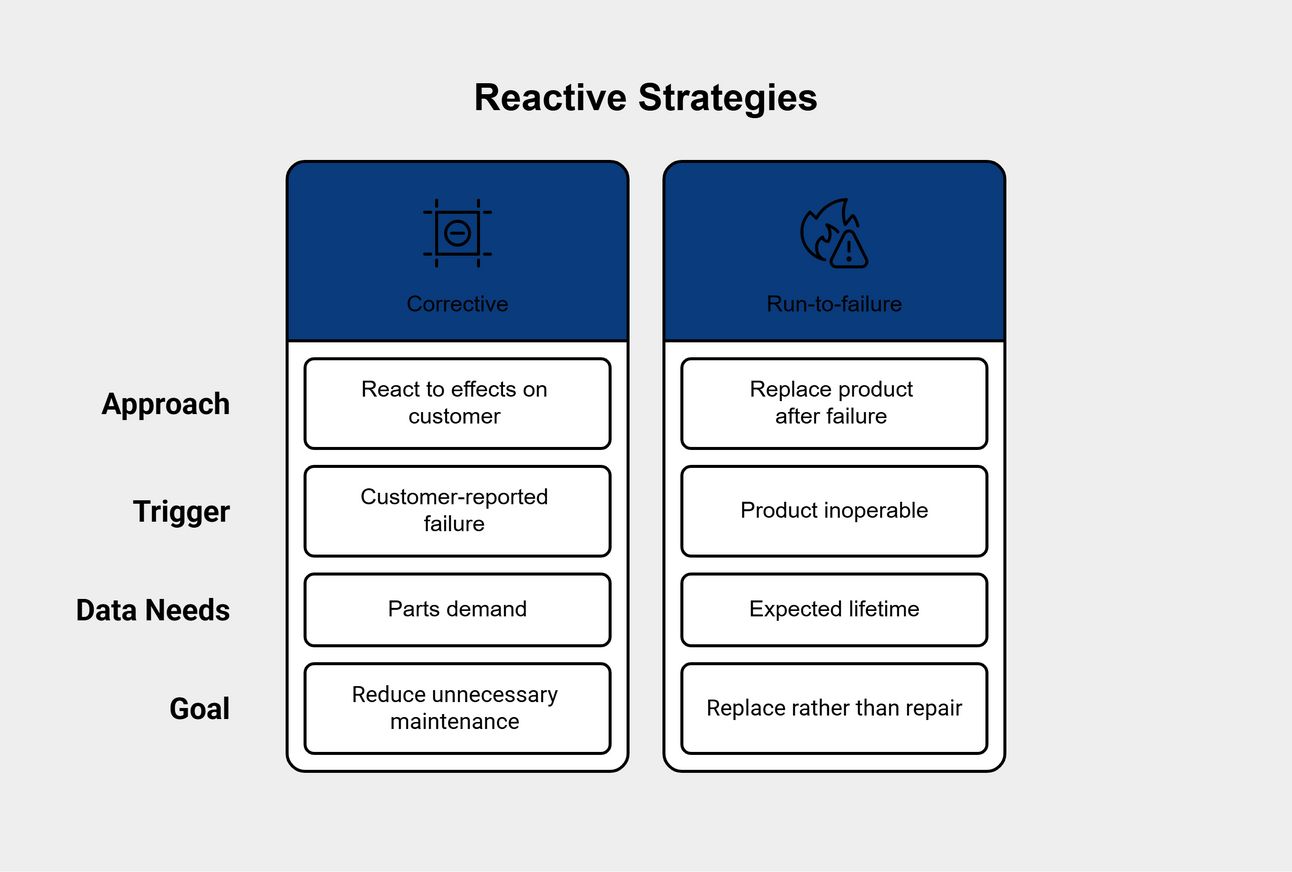

Reactive maintenance is intervention after the effects of the failure are felt. This may also be known as unplanned maintenance.

Corrective – this is what most people consider maintenance to be. After a user reports a failure, a specific action will be taken to repair or replace a specific part. Because this failure is directly impacting product availability to the customer, there is the greatest likelihood and impact of further maintenance-induced failures.

Run-to-failure – implies use past the point at which the effects are felt and up to the point at which the product is inoperable, potentially causing secondary failures elsewhere. Typical management of these failures is through replacement of the entire product.

The First Step

The first step to effective reliability centred maintenance is considering how maintenance will be performed while still at the development stage. Depending on how you decide your system will be maintained, you may want to consider different design options:

Corrective maintenance – modularity of parts, ease of access, redundancy

Run-to-failure – system cost, replacement availability

Preventive – harmonised part lifetimes, accelerated life testing

Condition-based – wear indicators, graceful failure

Predictive – telemetry, instrumentation for symptoms as well as causes

Design for reliability – life testing, design validation, FMEAs

Although this implies an increasing scale of better practice for maintenance, your product will have a blend of all maintenance approaches and increased focus on quality isn’t always worth it.

When designing your product you are laying the groundwork for the future success of the product. Key to this is balancing the trade-off between risks to the environment, safety, operations and costs. Designing in a considered maintenance regime is essential for a successful product, so take the first step now.